Kia ora! I’m Claire, the Science Outreach Projects Coordinator at Otago Museum. For the next month I will be working as the onboard outreach officer on the ship the JOIDES Resolution, for Expedition 378: South Pacific Paleogene Climate. I’ll be blogging about my adventures here, but you can also follow the ships social media accounts on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Blog Post Eight – The Tiny Keepers of Time

The cores are not what I expected. I’m not sure what I did expect, but after all the talk of mud I expected them to look, well, muddier. Most of the cores we have recovered are a brilliant white! White and kind of squishy and then, as we drilled deeper, white and kind of firm.

The white colour is because it is mostly composed of calcium carbonate, the remains of billions of tiny organisms that lived long ago. When they died, their calcium carbonate skeletons, or coatings, settled to the bottom and became the layers of sediment we are now recovering.

Image: A tiny piece of white nannofossil ooze sediment gets spread on a glass slide. Credit: Lindy Newman, IODP

This means good times for the micropaleontologists.

This is one of the first groups of scientists to get their eager hands on a piece of new core. They whisk this sample away to the lab where they try to identify exactly what microfossils are in it as soon as possible.

Onboard we have three flavours of micropaleontologists – we have the calcareous nannofossil team, the foraminifera team, and we have the radiolarian team. These groups are all sieving through the sediment to find their favourite kind of microfossil. These are tiny phytoplankton or zooplankton, the base of the ocean food web, that lived millions of years ago. They are single celled critters that lived out their short lives long ago. And, most importantly, they can help us date the sediment.

Image:The radiolarian Lamprocyclas matakohe, first described in Northland, NZ, is very common in the upper part of our cores. Credit: Dr. Chris Hollis, GNS

Within these groups of organisms there are many different types and species. And different species were alive at different times in the past. Matching up the species found in the sediment helps us to narrow in on the window of time we are looking at.

These fossils also record interesting things like tracking the progress of evolution after an extinction event. We see the loss of lots of species, but then new ones evolve out of what is left over. The advantage of using microfossils is that we can find lots of them, and there are lots of different kinds. The other advantage is that as they build their skeletons or coatings they pick up clues about what the Earth’s climate and the ocean environment was like at the time that they were alive, clues that the scientists can use now to answer different questions about ocean chemistry millions of years ago.

Image: Different kinds of Coccolithophores, tiny nannofossils that are found in fragments (left) or whole (right) in the sediment we recover. Credit: Rosie Sheward.

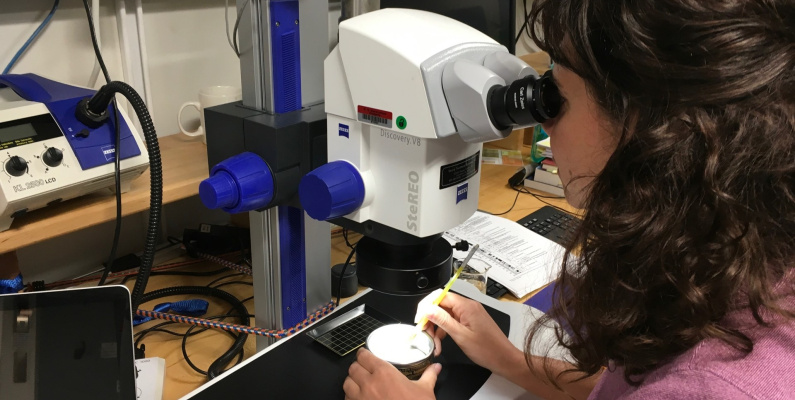

So, the minute the core gets brought on to the catwalk, this group will get a chunk of sediment from the end of the core. Straight away they will start processing it: The nannofossil team will take a tiny, toothpick amount of sediment, spread it on a slide and stick it under the microscope to look for different teeny-tiny fossils. The foraminifera team will take a bigger bit of sample and sieve it, then use a paint brush and a microscope to pick out the fossils they are interested in. The radiolarian team have to work a bit harder. Instead of calcium carbonate, radiolaria build their skeletons out of silica. So, this team has to first dissolve away all the calcium carbonate (get rid of the nannofossils and foraminifera) and then head to their microscope.

Why three different groups? Well, it’s a tricky job figuring out what time period the sediment is from. For each core that is brought to the surface the three groups will try to identify what species are present, compared to what is previously known about the geological time period those species were alive, write it up on a board and then have a hui. The board is suitably blazoned with the tag line ‘One board to rule them all, one board to find them, one board to bring them all – and in the darkness bind them’. This is the Board of Power, because knowing what age the sediment dates back to is vital for everything else that comes after.

Top Image: Flavia Boscolo Galazzo of Team Foraminifera tries to identify species present © IODP.