Canadian doctor Norman Bethune (1890–1939) gained his medical degree from the University of Toronto in 1916, and served with Canadian forces in World War I.

He joined the Communist Party of Canada after a 1935 trip to the Soviet Union. Canadian communists funded Bethune's medical work with the Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War in 1936–37. He gained a brief mention in New Zealand newspapers during that time. Under the headline, "Blood Transfusion; The Modern Technique; Lowering Mortality", the Evening Post reported that “Dr. Norman Bethune has organised in Madrid a service by blood donors who are fed but not paid. Blood is collected at base hospitals, conveyed to first-aid stations on the various fronts, where transfusions are effected”. [1]

Bethune is, however, better known for the last two years of his life. In early 1938 he travelled to China to aid the Communist Eighth Route Army in the second Sino-Japanese War. There, in Yan’an, he met Mao Zedong who assigned the organisation of a mobile operating unit to him. Bethune never returned to Canada. He died in China, on 12 November 1939 from the effects of blood poisoning from a cut incurred during an operation. He is buried in Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, China.

An essay written by Mao Zedong shortly after Bethune's death, described his selfless and responsible attitude: “Comrade Bethune's unselfish spirit, expresses his extreme feeling of responsibility towards his work and his extreme warmheartedness towards comrades and the people. Every Communist Party member must learn from him”. As one of “Three Constantly Read Articles”, an essay that formed part of a group of elementary reading materials in schools during the Cultural Revolution.[2]

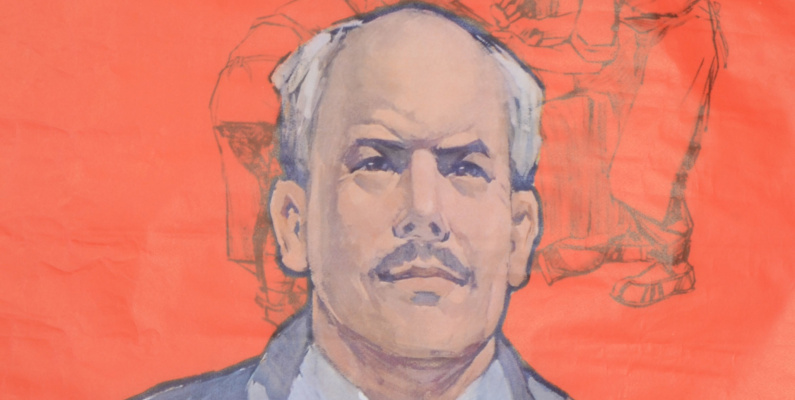

Image: 1968 poster showing the Canadian doctor, Norman Bethune (1890-1939), with a quotation from Mao Zedong's In Memory of Norman Bethune, first published in December, 1939. © Otago Museum.

His name was apparently evoked again during the 2003 SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak in China, when volunteers travelling to Beijing to assist were referred to as ‘Bethunes’. [3]

Elsewhere, current opinion about Bethune is mixed. He has a listing in the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame; [4] and other sources note that he was among the first to recognize the importance of prompt transfusion for the severely injured, citing his work in relation to the mobile blood transfusion service in the war in Spain.[5]

His career and personal relationships were, however, turbulent. Well-known Canadian actor, Donald Sutherland, played Norman Bethune in a 1990 Chinese/Canadian movie, Bethune: The Making of a Hero, filmed on location. Helen Mirren played Bethune’s wife. IMDb said of the movie:

“Canadian surgeon Norman Bethune journeys 1500 miles into China to reach Mao Zedong's eighth route army in the Wu Tai Mountains where he will build hospitals, provide care, and train medics. Flashbacks narrate the earlier events of his life: a bout with tuberculosis at the Trudeau sanatorium; the self-administration of an experimental pneumothorax; the invention of operative instruments; his fascination with socialism; a journey into medical Russia; and the founding of a mobile plasma transfusion unit in war-torn Spain. … By 1939, Bethune had been dismissed from his Montreal Hospital for taking unconventional risks and from his volunteer position in Spain for his chronic problems of drinking and womanizing. As his friend states: "China was all that was left." [6]

Near the end of the 1990s an edited volume of Bethune’s writing and art was published. [7] “With The Politics of Passion ... author Larry Hannant offers us the collected writings of a Canadian who, in many ways, is better known outside of Canada than in his homeland” wrote reviewer, Colin Leslie. [8]

Bethune remains controversial. The authors of a 2011 biography, Phoenix: The Life of Norman Bethune, went so far as to suggest that, “His deeds have been immortalized for political purposes, first by the government of China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, then by the government of Canada in the 1970s.” [9]

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Dr Lorraine Wong and Zhen Huang for their translation of the text on this poster.

Sources

[1] Evening Post, 29 June 1937, Page 7

[7] Bethune, N., 1998. The politics of passion: Norman Bethune's writing and art. University of Toronto Press.