Josephine Gordon Rich was one of only four New Zealand women to publish original scientific research in the 19th century. None were employed in universities, each wrote just a single article and lack of access to laboratories likely hampered further scientific investigation. [1]

Josephine held a unique interest in zoology that included illustration. At that time, painting in either oils or watercolours was a socially acceptable way for a woman to express an interest in the natural world. New Zealand attracted its share of talented women flower painters and botanical illustrators among its European settlers. Some at least found a way of earning their own money, although all eight of the generally recognised New Zealand women illustrators struggled to make a living. [2]

Josephine came from a middle-class background. Her English-born father William Gordon Rich was a runholder in Southland, a Justice of the Peace, and actively involved in local Anglican Church affairs, as an application to purchase five acres from the Land Board in order to build a church attests. [3] It’s possible that Josephine never had to earn a living.

She was certainly clever and topped first year classes in biology, zoology, botany and practical biology in 1891. [4] She does not seem to have graduated but University of Otago records are notoriously inaccurate over this period.

During her student years she contributed in a major way to the 1889 – 1890 New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition, an intercolonial show produced to commemorate the colony’s jubilee. Her mentor and teacher, Thomas Jeffery Parker, was responsible for the extensive natural history displays. Some animals could not be shown because they were either too small or too large. So, pictures and models replaced those that could not fit into glass jars, or were not available as stuffed or skeletal specimens. One reporter noted “five wall diagrams” and several drawings by Miss Gordon Rich, which he said “were instructive exhibits”. [5]

Image: VT2803. Sturgeon stomach preserved in alcohol. Otago Museum Collection. By Kane Fleury © Otago Museum.

Josephine's high-level of drawing skill was borne not just from the sort of ladylike practice encouraged as an accomplishment. Rather, it came from directly dealing with the animals she worked on. She dissected her own creatures, stained the tissues and examined them under the microscope. The Museum’s collections hold jars containing the stomach of a sheep, a sturgeon (a primitive fish) and a kiwi preserved in alcohol. These specimens suggest she collaborated closely with Parker on his pioneering preservation methods using hot glycerine.

Image: AV10572. Kiwi digestive tract. Otago Museum Collection. By Kane Fleury © Otago Museum.

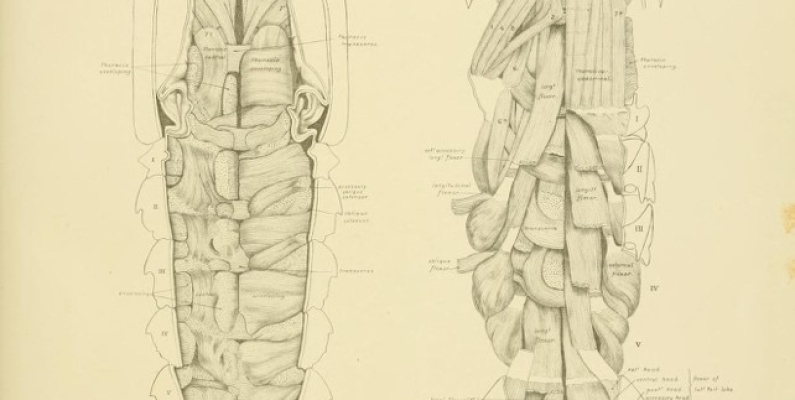

Together they undertook research on the musculature of crayfish and published a paper in 1893. [6] Once again her drawing skills came to the fore and a reviewer of the volume in which it was published noted the “remarkably clear” plates that accompanied the article.

[1] Rosi Crane, “Rich Pickings: the intellectual life of Josephine Gordon Rich (1866-1940).” Journal of New Zealand Studies 24 (2017): 57-71.

[2] Bee Dawson, The Lady Painters: The Flower Painters of Early New Zealand (Auckland: Viking Penguin Books) 1999, pp. x-xi.

[3] “The Land Board”, Evening Star, 13 February 1884, p.2.

[4] “University of Otago,” Evening Star, 5 November 1891, p.4.

[5] “The South Seas and Early Court History etc” Otago Witness, 28 November 1889, p.21.

[6] Parker, T Jeffery, and Josephine Gordon Rich. “Observations on the Myology of Palinurus edwardsii, Hutton.” In Macleay Memorial Volume, edited by J J Fletcher, 159-77. Sydney: Linnean Society of New South Wales, 1893.

Top image: Plate drawn by Josephine Gordon Rich, published 1893.