“What is that?” is a question I receive often. As a scientist who studies marine invertebrates and now lampreys (the topic of my PhD thesis) I am used to receiving looks of disgust, shock, and — in the case of my aunt — horror when I describe my study organisms. So, it has become somewhat of a mission of mine to try to raise awareness and to get people to avoid ‘judging a book by its cover’ or in my case, a specimen jar by its looks.

Rori/Sea cucumbers, Australostichopus mollis. VT9888. Photo Kane Fleury, Otago Museum

When I first started volunteering with the Museum in 2020, I began by helping the curators update their geodatabase. By refining the area where a collection item was collected, I was helping to update the Museum catalogue system so that researchers inquiring about the collection remotely would know the approximate geographical location of where collection material was found and be able to easily place it onto a map. The locality information of biological specimens in particular, is extremely important as researchers often use the location of a specimen to help identify what population it belongs to. Sometimes this locality information can even help researchers identify if an organism is a new species. Therefore, specimen catalogue information, such as this locality information, is extremely important for keeping track of the history, or story, of each individual specimen in the museum.

A lovelier live deep-sea cucumber I found off Costa Rica. Photo: Allison Miller

Recently, Museum Curators and I began cataloguing and updating the information with the specimens in the museum’s sea cucumber collection, which was in need of some refreshing. Rori (sea cucumbers) are one of the lesser-known relatives of the papatangaroa (sea stars) and kina (urchins). They are a diverse group of echinoderms, and fortuitously, I happen to be well educated in their biology, systematics, and genetics since they were the topic of my University of Guam master’s research. So, my current mission is to go through multiple ‘vouchers’ (the word for the representative specimens of a species) of ethanol-preserved sea cucumbers to verify their identification and update their catalogue information.

Enter: the jars

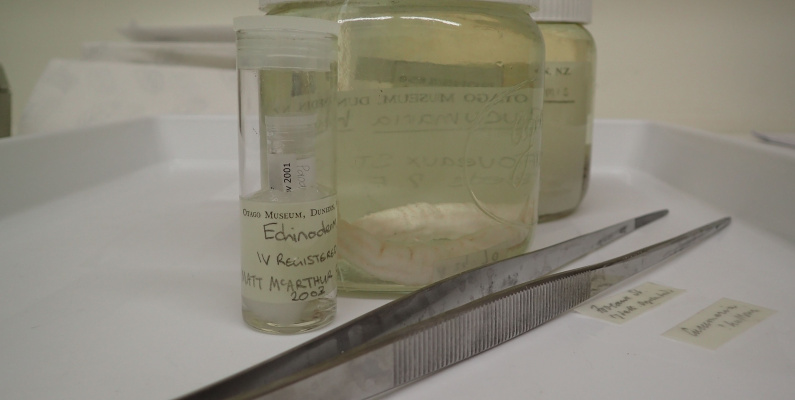

Many soft-bodied invertebrates at the museum are stored ‘wet’ in jars, and I have to admit, most of these specimen jars are not the prettiest things to look at. It also does not help that jars like this are popular props in horror movies. Often, they contain discoloured, shrivelled or bloated organisms (an effect of the preservative solution), floating in an off-coloured liquid, that smells of isopropyl alcohol mixed with biological material (an oddly almost sweet smell). But there is more to these jars than meets the eye, or sometimes the nose.

Jar of clues: One leathery colourless “cuke”, with basic location data, original accession numbers and a past identification label. Photo: Allison Miller, Otago Museum.

Each of these specimens tell a story. A story about the specimens themselves — where they are from, what habitat they like, how they behave — but also about their collectors — where they had to travel to and what they had to go through to get these specimens. Personally, I know the difficulty of collecting specimens from remote places such as the Northern Marianas Islands and the Raja Ampat Archipelago of Indonesia. It is no easy task, a lot of work and time goes into collecting, preserving, storing, and relocating the specimens. And of course, we cannot forget the ultimate sacrifice of the specimens themselves. Sometimes even the physical jars tell a story, as sample jars were hard to come by in the 1800s (and earlier) and had to be handmade and sealed with things like bitumen (asphalt).

Out of their jar: A peck of pickled sea cucumbers, IV134341. Photo : Kane Fleury, Otago Museum

This line-up of wee sea cucumbers were collected in 1908 by Walter Reginald Brook Oliver during a 1908 expedition to Rangitāhua, Kermadec Islands. In 1908 there were no high-speed jets, air planes, or fancy research cruise ships (and I do mean fancy... some of the research cruise ships I’ve worked on — I won’t state which one, but it rhymes with Smoogle — even had saunas!). Researchers like Walter Oliver had to voyage for weeks on rough seas, through storms, and likely eating bland food, to finally get to the Kermadec Islands where these specimens were collected. Once at the islands, scientists likely had to venture out to remote regions for their collections and then would return to their ship where they would spend hours counting, dissecting, and recording morphological information about the specimens they found. They spent almost a year on the islands documenting the biodiversity and geology of the islands. After the expedition, many of the specimens collected were sent out to other museum curators and scientific experts to describe the species that expedition team members were unable to identify.

The information about these Kermadec Island’s sea cucumbers was not digitally catalogued before Otago Museum curators and I updated their information. Now researchers from New Zealand, and all over the world, will be able to more quickly access the information about these sea cucumbers, understand their story, and be able to incorporate them into their research. If time allows, we may even be able to take small bits of tissue from these sea cucumbers and build a genetic catalogue for researchers to use. This way researchers can collect DNA from sea cucumbers in the wild and will be able to tell quickly, and with certainty, which species they have. This genetic catalogue would be particularly helpful to researchers that are now using environmental DNA (or eDNA) in their studies and will lead to a better understanding of ocean biodiversity around New Zealand and across the globe.

My in-tray. Photo: Allison Miller, Otago Museum.

So, what’s in a jar? When I see a specimen jar, along with the pickled organism, I see adventure, sacrifice, opportunity, and untold stories. Hopefully now if you come across one of these jars you will see this too. And hopefully you will appreciate, as I do, all of the work and effort that went into collecting that specimen and understand the importance of keeping it well documented.

This blog was written to commemorate National Volunteer week 2021. We would like to thank all the volunteers like Allison that donate their time and expertise to Otago Museum’s mahi.