Kia ora! I’m Claire, the Science Outreach Projects Coordinator at Otago Museum. For the next month I will be working as the onboard outreach officer on the ship the JOIDES Resolution, for Expedition 378: South Pacific Paleogene Climate. I’ll be blogging about my adventures here, but you can also follow the ships social media accounts on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Blog Post Seven – Feeling the flow

We’ve reached our site and have started drilling! When core comes up from below it arrives first on the drill deck, where the drillers will lift out the massive drill pipe and pull out the plastic core liner that contains the sediment. Once the core arrives on the drill deck, the driller will announce ‘Core on Deck’. There was so much excitement on board when the first core arrived up! But it was quickly followed by another core, and then another, and another!!

Image: Love the smell of fresh core in the morning. Nine metre length of core sits on the catwalk ready to be cut. By Claire Concannon © Otago Museum.

Depending on the type of material they are trying to recover (is it rock, is it mud, is it ooze?) and the depths they are recovering it from, new cores, 9 m long in cylindrical plastic liners, can be brought up from the seabed floor back to the ship as frequently as every 20 minutes. Once the core is on deck, it gets lifted and walked by the techs to the catwalk. Here it gets sampled by the chemists and micropaleontologists, who quickly head back to their labs to work on these samples. Then it gets cut in to 1.5 m lengths, which are brought in sequential order into the lab and are labelled.

Some quick maths here: 9 m cores divided by 1.5 m = 6 per Core on Deck. Standard depth for the first kind of drilling kit used, an advanced piston core (APC) is 240 m, lets conservatively round it down to 225 m so that the numbers are nice… That means that we would get 150 core segments per APC drill site. We plan to drill three sites, so we are up to 450 now, and we are also going to drill deeper, down to at least 600 m, though often recovery of the hard rock at deeper depths is poorer, so let’s conservatively say that it’s just another 200. We are at 650.

650 separate pieces of core.

Image: The rack in the core lab filling up with pieces of core! By Claire Concannon © Otago Museum.

So, once those magical words get announced over the intercom ‘Core on Deck’, they kick off a well regimented set of actions by techs and scientists on board to process all this core: The Core Flow.

Core flow begins with a vital first step, labelling. These cores are useless if they are mixed up or mislabelled. So not only are paper labels added, but a label is also laser marked onto the plastic core liner. The cores then need to sit for a while, to equilibrate to the temperature in the lab (remember they’ve come up from hundreds of metres below the seafloor!). Then they get picked up by the scientists who are in the physical properties team (phys props if you are down with the lingo) who start ‘running tracks’ (more lingo….). This means that the cores are put onto automated tracks that run them through machines to x-ray them, and to study their density, their magnetic susceptibility, and their natural gamma radiation.

Once these ‘whole round’ measurements are complete, the core gets split along its length (so double the number you are dealing with now!!). This gives two identical halves along the timeline of that core. One will be the ‘working half’ – scientists from the expedition will get to take samples from this half both now and at the post-cruise ‘sample party’ (more on this later!). The other will be the ‘archive half’ – this will be described, photographed and measured on the ship but left untouched. After description it will be stored away, until it can be transported to one of the International Ocean Discovery Programme core repositories (also more on this later!).

Image:Studying and sampling the ‘working half’By Claire Concannon © Otago Museum.

Both working and archive halves go under the scrutiny of the core describers. They take notes on what is in the core (ooze, chalk, rock etc.), the colour of the core (using a colour palette booklet like you would use if you were picking paint!), and any interesting features of the core. They also take photographs along the length of the core, and look at smear slides of the material under the microscope to work out what it is mostly composed of.

Image: Nannofossil ooze white is colour of choice this month on the JOIDES Resolution.By Claire Concannon © Otago Museum.

The last thing that happens to these core halves before they are boxed away for future sampling (working half) or storing (archive half) is to put them through the super conducting rock magnetometer. This will identify whether the magnetic field of the Earth was as it is now or reversed at the time the sediment was laid down. This will assist in dating the cores, because we can line up the flips in magnetic field with what we already know happened in geological time.

But it’s not the only thing used to date the sediments. Remember I said the micropaleontologists took samples first thing? They are also working away to date the cores, but you’ll have to wait for the next blog post to find out how……

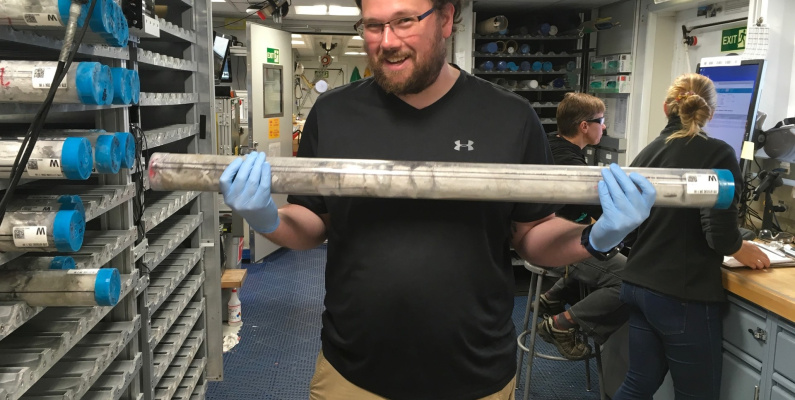

Top Image: Alex is part of the phys props team, who works out every day by lifting and carrying cores to and from different machines. By Claire Concannon © Otago Museum.